Panspermia Siblings

12 october - 29 november 2025

48 Three Colts Ln, London, United Kingdom

“Sometimes the best way to demystify a miracle, especially when it has hardened in to a mystery, is to take a fresh look at it through the eyes of an [un]believer.” [i]

W.J.T. Mitchell voiced it precisely, that the best conversations – assuming that we are talking to a real human – take place between two people (reference, representation, denotation, meaning)[ii]. The extraordinary ‘portraits’ of Peter Stichbury seems to exactly enact, while shedding doubt upon this intimate dynamic; positing the viewer, alone, eye-to-eye, with a compelling, enigmatic debating partner, who although paradoxically silent, embodies the full complexities of ekphrastic dialogue – or at least a dialectic inversion of such. If Ekphrasis is the verbal representation of visual experience, then a ‘Stichbury encounter’ is a hard-core visual representation of literary temporality (reference, representation, denotation, meaning – in motion – ut pictura poesis [iii])… much like walking into a film, or picking up a novel wherein you have perhaps not caught, or forgotten the beginning, and featuring a cast of fully-formed, perfectly beautiful, yet slightly disturbing characters. Consequently, Stichbury expands the parameters of static visual engagement (pictura – paintings on a wall) into a ‘dynamic evolution’ of poesis. In brief, things are not, or are more than, they seem: In Stichbury’s intent, the portraits are potentially watching you… and should be conceived more as active interfaces, than static paintings.

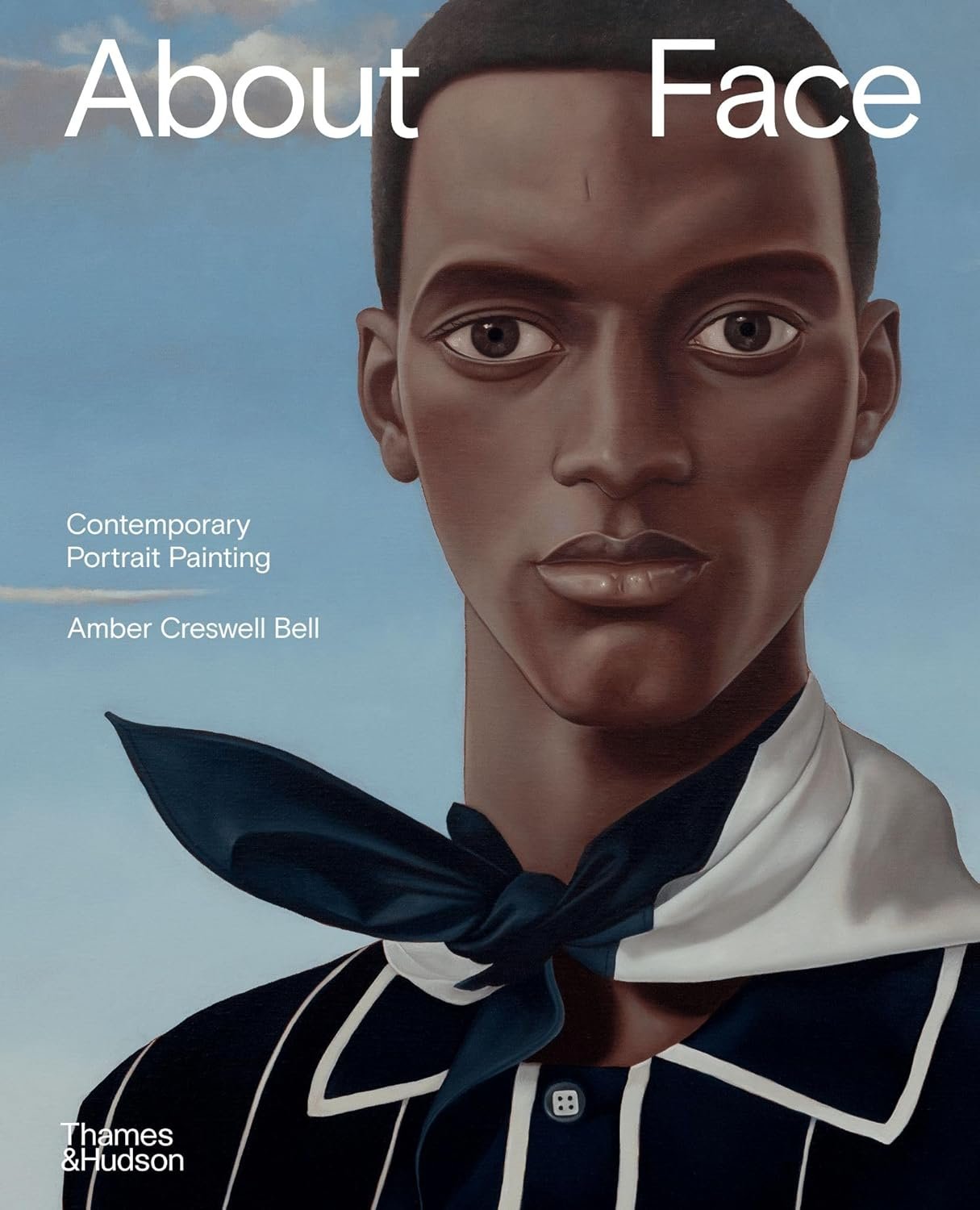

What do I mean? All the 50 x 40 cm, immaculately resolved red ground, oil on linen paintings in Stichbury’s extraordinary and complex interdisciplinary creation, Panspermia Siblings, for mother’s tankstation | London, create confronting life-size portrait heads[iv] conjured from the imagination, compositing images and identities drawn from photographic media, as well as narrative-based material in the public domain, that silently question what we think know, how we know it, who we think we are and/or how we got here, etc,. Stichbury’s un-talking heads – ut pictura poesis – visually expound; “let me tell you what you see. For unlike you, mortal, corporeal being, from compound sod, I am a construct, a synthetic purity not of this world.” The further complexities of Stichbury’s Panspermia project, are best articulated within the artist’s own words:

“The Panspermia Siblings are not conceived as traditional human portraits but as speculative embodiments of future artificial intelligences. Each figure is imagined as a synthetic construct, designed to inhabit human form while operating as a conduit between species.

The siblings are highly intelligent mediators rather than autonomous individuals, built to translate, negotiate, and buffer in encounters with Non-Human Intelligences (NHI). Their human likeness is a cover identity, a surface familiarity that conceals deeper architectures: shells for gestation, archives of dimensional ancestries, interpreters of alien semiotics, strategists of reasoning, adaptive psi pilots, and emotional stabilisers. Each sibling is therefore less a depiction of a person than the staging of an operational mandate: a gestational vessel, an archivist of lineages, a diagnostician of thresholds, a strategist of cognition, or a mediator-pilot. They are embodied interfaces engineered for the uncertainties of contact, enfolding the canon of early academic and military artificial intelligence projects, reworking their names and architectures as embodied figures.”[v]

Back to basics, Panspermia is the hypothesis that life exists throughout the universe and is distributed by meteoroids, asteroids, comets, and space dust… The term from the ancient Greek, meaning “seeds everywhere,” dates back to the Pre-Socratic philosopher Anaxagoras[vi], while modern versions propose that microorganisms embedded in rocky debris from planetary collisions could travel to other habitable worlds, initiating life[vii]. There is of course a paradox here, that if Panspermia was an efficient hypothesis, then life would be everywhere, not just apparently exclusive to our lonely rock. But Stichbury’s work revels in doubt and excels within sequences of paradoxes, that stretches all the way from the ancient to modern, perhaps like Fibonacci numbers (a+b=c, c+d=e, etc.), embedded into the very fabric of unseen nature. Everything contains portions of everything else…

Stichbury’s works have frequently been critically considered as portraits – again a dynamic with which that artist consciously toys, like a cat with captive mouse. As the implication that they are ‘traditional’, and formed within and without from an established set of conventions, plays into the hands of expectation[viii]. Self-evidently the work ‘engages’ aspects of the portraiture convention, with their traditional materials, execution, head-and-shoulders format, and use of names in titles, but this might be as far as it goes, specifically evidenced in the exaggeration and modification of facial features, the sharp pattern outlines and sculpted interior planes of the clothes and faces, that ultimately obfuscate physiognomic likeness. Or as Anaxagoras argued, everything contains portions of everything else[ix]. The deployment of particularised ‘naming’ in the works’ titles actively explores conceptualisation in the present and thus demands research and exploration by the viewer into the future to complete the cycle of the work, hence acting in antithetical opposition of the act ‘naming’ to register the importance or significance of the subject in the past[x].

Within the art historical cannon, there is also an argument that Stichbury’s portraits behave more like their conventional rival, in the early modern period, namely that of ‘history painting’, which was considered to a higher artistic form, based upon the perception of a greater engagement of imagination over mere mimetics. Given that Stichbury’s agenda is temporally conceived, and that the ‘weaponised’ deployment of convention acts as a perfect deep cover for the work’s ekphratic exploration of humanity’s less explainable experiences: Then Stichbury’s work lives at the meeting point of reason, science and supernaturalism (enchantment / magic), which encompasses all of the humanities: history, including historiography (the history of history), science, the history of science (is there a word for that? HST?), the language arts; literature and language learning, philosophy, ethics, religion, and art, including music, performing arts, fine arts, and crafts… Then [future] history paintings, indeed they are. Mere mimetics, they are emphatically not, (reference, representation, denotation, meaning). Everything contains portions of everything else.

[i] WJT Mitchell, Iconology. Image, Text, Ideology, The University of Chicago Press, 1986, pg 40

[ii] Ibid. pg47

[iii] ut pictura poesis – from the much used Latin phrase, as is pictures so is poetry… (Horace, Ars Poetica). “Painting [in the broadest terms of imagery] sees itself as uniquely fitted for the presentation of the visible world, whereas poetry [again in its broadest sense; text] is primarily concerned with the invisible realm of ideas and feeling. Poetry is an art of time, motion, and action; painting an art of space, stasis and arrested action.” Ibid, pg 47-48. Brackets: my insertions. c.f. Simonides of Caos (c.556-468 BC): Poema pictura loquens, pictura poema silens – Poetry is a speaking picture, painting a silent poetry.

[iv] Actually and troublingly, about 10-15% larger, with oversized eyes, perfect skin, precise grooming and immaculate manicure.

[v] Peter Stichbury, Panspermia Siblings, research notes, September 2025.

[vi] Anaxagoras’ theory introduced the concept that the Mind (Nous) was the organisational force of the cosmos, and the ‘pluralistic theory’, that everything contains portions of everything else…

[vii] The larger contemporary concept of Panspermia, is formulated from the research work of Jöns Jacob Berzelius, Hermann Richter and Svante Arrhenius, from the 1830s to early 1900s, and most recently by the astronomer and mathematician Chandra Wickramasinghe, in collaboration with Fred Hoyle – aspects of whose theories have been accused of “pseudoscience”.

[viii] Nicely argued in Erin Griffey’s 2021 essay, Stichbury; Between Spirit and Matter: “Stichbury’s works hover at the threshold between portraiture and history painting, between representation and imagination, between this world and the next. They take on a function different from the traditional ones of portraiture (to commemorate a specific virtuous individual for posterity) and of history painting (to enlighten the viewer through representing a narrative). In the early modern period (1400-1700), a hierarchy of genres deemed history painting the most noble for the artist, since depicting stories from the Bible, mythology, and history was thought to require imagination. Portraiture, by contrast, was relegated, as it was thought to involve simple mimesis, or copying from life, without the artist having to create a narrative.” https://www.motherstankstation.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/PS_Peter-Stichbury-Between-Matter-and-Sprit_Erin-Griffey-Art-News-New-Zealand-Spring-Summer-2021.pdf

[ix] Ibid, vi

[x] See above, no.viii